What is currency hedging & what does it mean to me?

In this article, when we say hedging, we mean currency hedging – not some crazy hedge fund manager punting pork belly futures.

Currency hedging only affects investments that are not in Australia.

If all of your investments are only in Australia (which are in $A), currency hedging doesn’t matter.

In a nutshell

If the $A is falling, you prefer your investments unhedged.

When the $A is rising, hedged is your better option.

Currency Conversion 101

If the $A/$US exchange rate is 66c, that means that one Aussie dollar will only buy you US66c.

The flip side of this is $US/$A, which means that if you have one US dollar, it will buy you $A1.52.

Unless otherwise noted, we will use the $ A/$US conversion for the sake of this article.

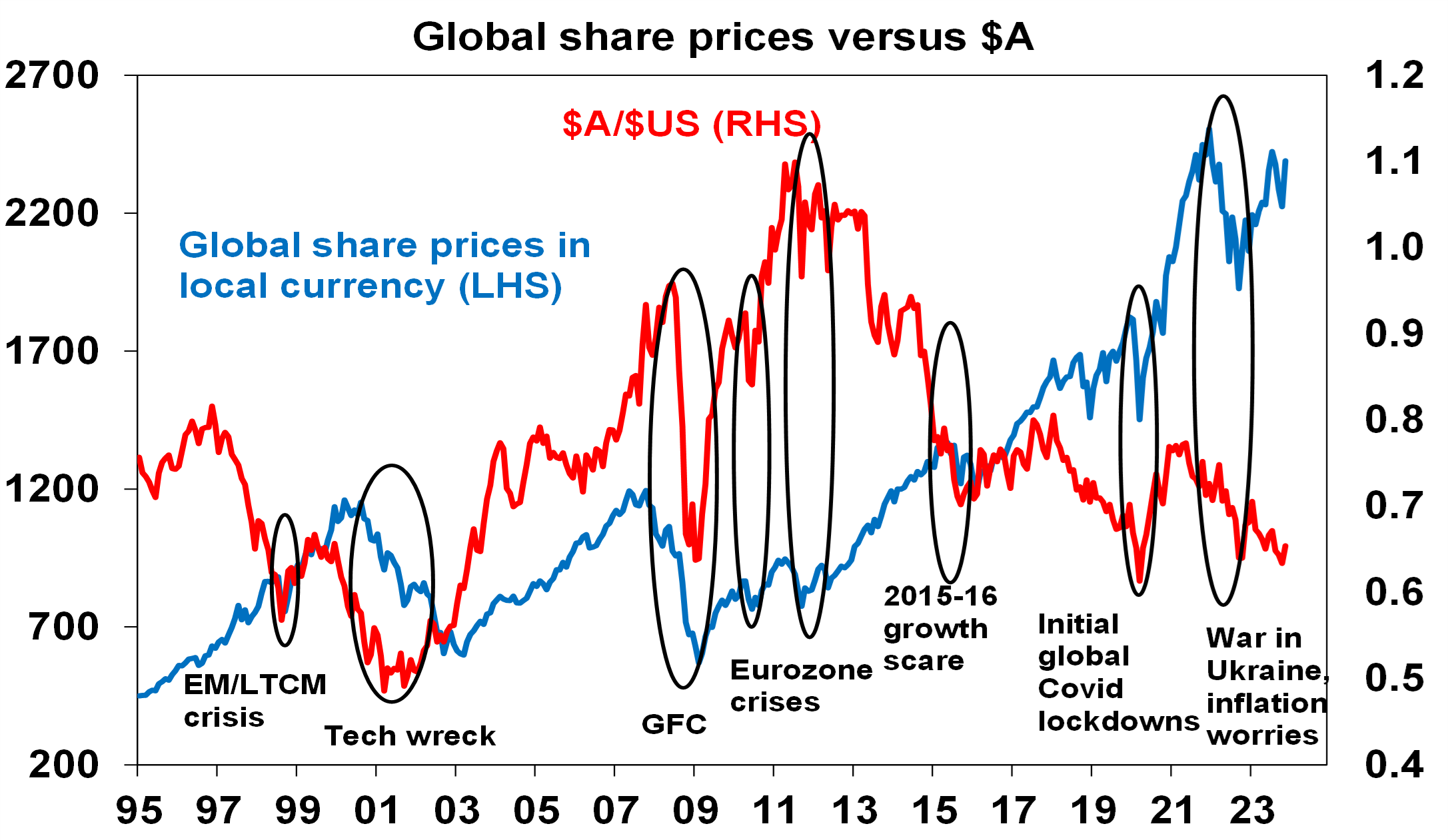

$A/$US movements

Back in 2014, the $A/$US exchange rate was 78c.

This time last year, it was around 67c; three years ago, it was 73c, and today, it’s 66c.

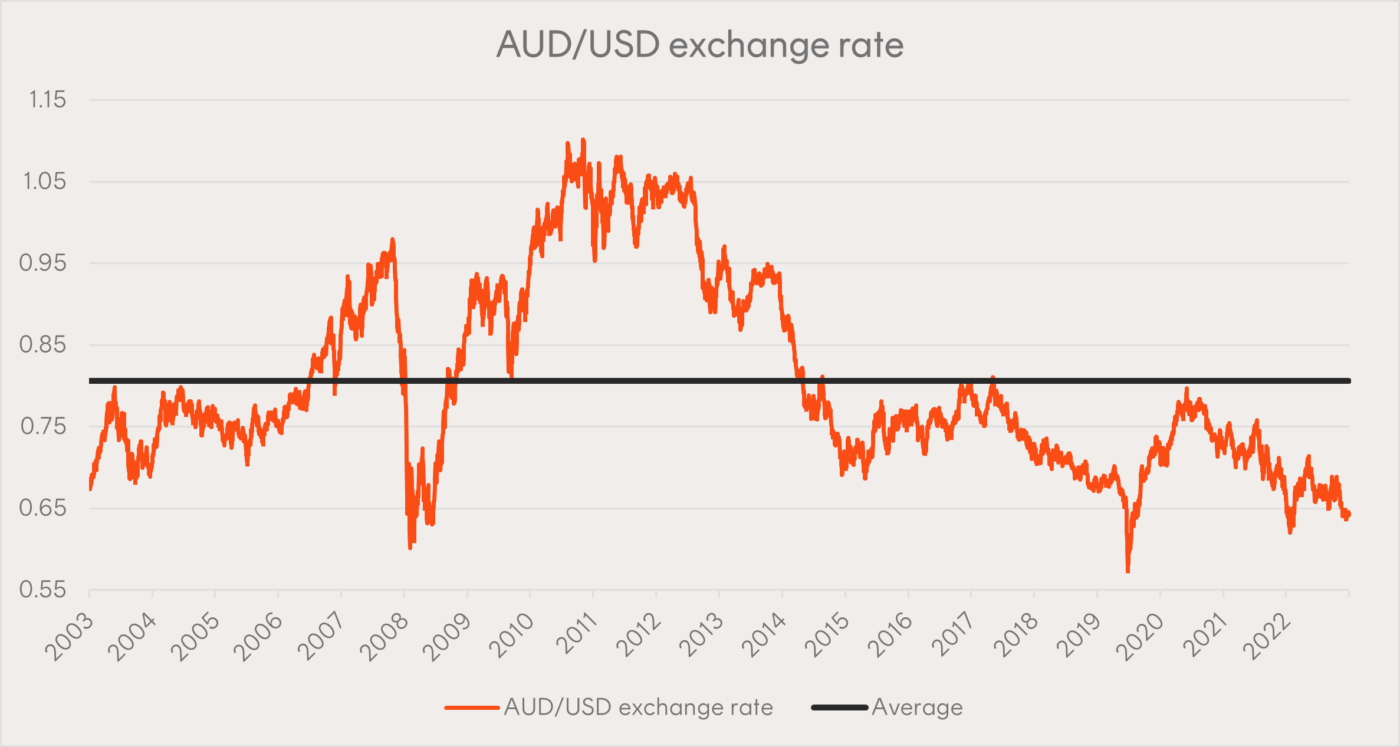

The long-term average exchange rate has been around US81c, as shown in the chart below.

Historically, we have observed US65c as a key level for investors considering whether to start thinking about currency-hedged options.

The $A recently fell below this mark for just the fifth time in the past 20 years.

The long-term average exchange rate has been around US81c.

If the $A reverts to the mean (US81c) from US65c, investors in unhedged $US exposures would suffer.

Why does it matter?

The decision to hedge your currency exposure is important, as movements in the Australian dollar can either erode or add value to your investment.

If the $A were to decline by 10% relative to the $US, the value of investments denominated in US dollars would typically increase by 10% in $A terms.

If the $A starts to rise, as many analysts are predicting, you are better off with currency-hedged options. So, if our currency rises, you make more money if you are hedged rather than unhedged.

For example, if you have an ETF with a holding in Microsoft, $US 100 of Microsoft shares would right now be worth $A152.

If the exchange rate increases to US75c, your investment in $A would now be worth $A133.

[For income-oriented investors, hedging ensures currency movements do not offset offshore income.]

Which way are we expecting the $A to go?

Since its February 2021 high of nearly US80c, the $A has fallen on worries about the global growth outlook, China, the strong $US, and the RBA’s relatively less aggressive monetary tightening.

However, according to Dr Shane Oliver, AMP’s Chief Economist, there is good reason to expect the $A to rise as:

- It’s undervalued;

- Short-term interest rate differentials look likely to shift in favour of Australia. That is, we expect that the US will reduce interest rates sooner than Australia;

- Sentiment towards the $A is negative;

- Commodities still look to have entered a new super cycle; &

- Australia has a solid current account surplus.

So, there is a case for Australian-based investors to tilt a bit to hedged global investments.

The main downside risk for the $A would be if there is a hard landing globally and/or in Australia next year.

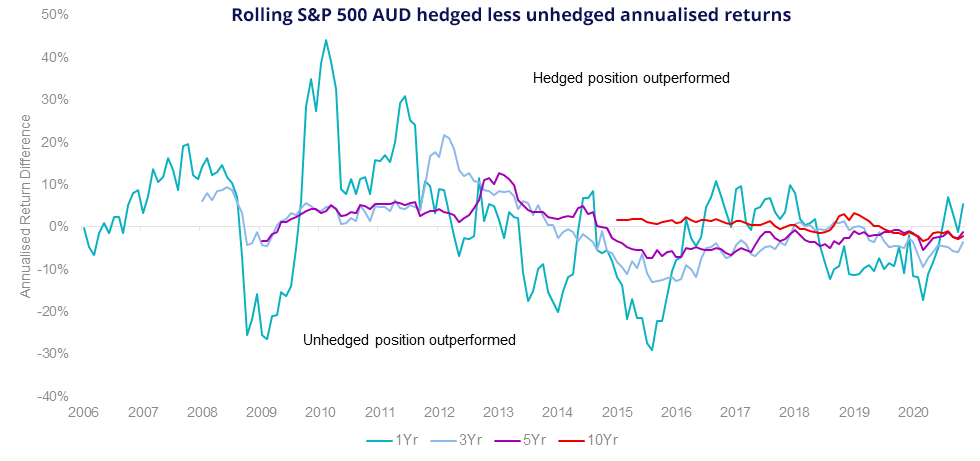

It’s important to remember that, over the long run, currency risks generally even out.

What options do investors have for currency hedge portfolios?

Given this weakness in the $A, how should investors think about their currency exposure?

Currency-hedged ETFs seek to substantially offset a fund’s exposure to movements in the value of foreign currency.

For example, any drop in the $A helps unhedged investors as it magnifies gains when assets are converted back into Australian dollars.

This is where hedging an international portfolio may be advantageous, as it will benefit from rises in the value of the $A.

Risks

Ultimately, much like investing, timing currency exposure is difficult to assess.

Investments carry risks such as ASX trading time differences, financial markets generally, individual company management, industry sectors, foreign currency, currency hedging, country or sector concentration, political, regulatory and tax risks, fund operations, liquidity and tracking an index.

Let’s wrap this up then.

When investing in international assets, an investor has the choice of being hedged (which removes this currency impact) or unhedged (which leaves the investor exposed to $A changes).

For Australian-based investors, if the $A is falling and you have unhedged investments, you make money on the currency devaluation.

Conversely, if the $A is rising & you have unhedged investments, you are losing money on the currency appreciation.

The decline in the $A over the last few years has enhanced the returns from global shares in $A terms.

So, given expectations for the $A to rise further into next year there is a case for investors to tilt towards a more hedged exposure of their international investments.